The aloha shirt is something that just about everybody knows. It’s become a cliche by now, having been around for about seventy years, and represents the most outwardly obvious souvenir of Hawaii that anyone has ever taken home. The aloha shirt, as one writer described it in 1953, is “like a postcard you can wear”.

The aloha shirt is something that just about everybody knows. It’s become a cliche by now, having been around for about seventy years, and represents the most outwardly obvious souvenir of Hawaii that anyone has ever taken home. The aloha shirt, as one writer described it in 1953, is “like a postcard you can wear”.

Where did all these wonderful designs come from? The made jumble of things like Diamond Head and Aloha Tower, the garish, the sometimes bizarre flowers, the strange fish entwined in undersea plants, the surfers and canoe paddlers and hula dancers, the palm trees, the ukuleles, the helpful Hawaiian words sprinkled throughout — in short, all stereotypical Hawaiian images — where did they all come from? Answer: from designers too numerous to name, even if they all were known, who were inspired by the beauties of Hawaii. The original ones actually worked in the islands, but later there were many others employed by manufacturers in Japan and the U.S.A. who jumped on the bandwagon around 1950 when alohawear became an international craze.

It had all started some years before that, though. In the early 1930s, the more adventuresome members of a younger island-born generation began to appear in shirts they’d had made from brightly colored Japanese silks and cottons. Such fabric was traditionally used in Japan only for young children since its riotous hues were considered inappropriate for adults, but restrictions like these were ignored in Hawaii. By 1935, such shirts werre a fad for young people of all races. Before long, serious designers began to produce fabrics with Hawaiian themes, and the “aloha shirt” had arrived.

It had all started some years before that, though. In the early 1930s, the more adventuresome members of a younger island-born generation began to appear in shirts they’d had made from brightly colored Japanese silks and cottons. Such fabric was traditionally used in Japan only for young children since its riotous hues were considered inappropriate for adults, but restrictions like these were ignored in Hawaii. By 1935, such shirts werre a fad for young people of all races. Before long, serious designers began to produce fabrics with Hawaiian themes, and the “aloha shirt” had arrived.

By 1939 the garment industry was flourishing, with much of its output intended for tourists. Local residents gradually took to this festive clothing too, helped by the invention of Aloha Week in 1947. During this yearly celebration of Hawaiian activities, every company urged its employees to sport the most brilliant alohawear they could find. The response was so enthusiastic that over the next decades such informality at work became the rule in Hawaii.

By 1939 the garment industry was flourishing, with much of its output intended for tourists. Local residents gradually took to this festive clothing too, helped by the invention of Aloha Week in 1947. During this yearly celebration of Hawaiian activities, every company urged its employees to sport the most brilliant alohawear they could find. The response was so enthusiastic that over the next decades such informality at work became the rule in Hawaii.

By the 1960s, the lavishly illustrated type of print with every possible Hawaiian motif thrown together had come to seem tacky and outdated, and manufacturers shunned it. But around 1970 such fabrics slowly began to creep back into style with the help (again) of the more adventuresome members of the younger and hipper set. This time the old shirts were dubbed “silkies” (even though they were made of rayon), and they eventually became prized possessions. You only rarely see old silkies around anymore since most have passed through their second stage of usefullness by now, but if you do , you’ll find it hard to believe that such an amazing garment would’ve been available for an unbelievable 75 cents new in 1936.

The alohawear era really began in 1936, when some local manufacturers got the bright idea of making ready-to-wear shirts for tourists who couldn’t wait several days to have one tailormade. One such businessman, Ellery Chun, registered the term “aloha shirt” that year as a variation on the numerous other “aloha”-named items meant for tourists. Shown here is a later version of the historic clothing label that, in effect, named an entire industry. The name of Chun’s store, King-Smith, is featured as the “creator” of the title.

The alohawear era really began in 1936, when some local manufacturers got the bright idea of making ready-to-wear shirts for tourists who couldn’t wait several days to have one tailormade. One such businessman, Ellery Chun, registered the term “aloha shirt” that year as a variation on the numerous other “aloha”-named items meant for tourists. Shown here is a later version of the historic clothing label that, in effect, named an entire industry. The name of Chun’s store, King-Smith, is featured as the “creator” of the title.

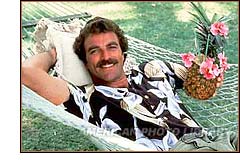

Another pioneer in the field was George Brangier, seen below with a female assistant handling the new clothing craze. Brangier and his partner Nat Norfleet started their company, Branfleet (later Kahala Sportswear), in 1936. All the shirts were made from traditional Japanese cloth, the predecessor to the Hawaiian designed fabric that would appear around 1937.

Alohawear’s popularity outside of Hawaii peaked in the 1950s when even mainland manufacturers were designing “Hawaiian” print sportshirts. Frequent publicity regarding Hawaii’s attempts to gain statehood all through the decade probably helped to make people aware of the islands and their fashions, but movies undoubtedly played a bigger role. “From Here To Eternity” dressed its principal male actors like Frank Sinatra and Ernest Borgnine in a succession of aloha shirts that more accurately reflected the fashions of the year the film was made (1954) than the year in which it was set (1941). Here’s a photo of a tense scene which takes place between “hostess” (in the book: prostitute) Donna Reed and angry soldier Montgomery Clift, clad of course in the necessary tropical print shirt.

Alohawear’s popularity outside of Hawaii peaked in the 1950s when even mainland manufacturers were designing “Hawaiian” print sportshirts. Frequent publicity regarding Hawaii’s attempts to gain statehood all through the decade probably helped to make people aware of the islands and their fashions, but movies undoubtedly played a bigger role. “From Here To Eternity” dressed its principal male actors like Frank Sinatra and Ernest Borgnine in a succession of aloha shirts that more accurately reflected the fashions of the year the film was made (1954) than the year in which it was set (1941). Here’s a photo of a tense scene which takes place between “hostess” (in the book: prostitute) Donna Reed and angry soldier Montgomery Clift, clad of course in the necessary tropical print shirt.

“To arrive in Hawaii … and then to switch abruptly into one of those kaleidoscopic shirts in violent reds and wild blues and insane yellows … that is no procedure for a sensitive man to follow.”

–Waikiki Beachnik, 1960

*Loosely adapted from a book on Hawaiian nostalgia.

You mention that in the film “From Here To Eternity” the dressing of the “principal male actors…in a succession of aloha shirts that more accurately reflected the fashions of the year the film was made (1954) than the year in which it was set (1941)” is inaccurate on two counts. The film was released (and won the Best Picture Oscar) in 1953, not 1954. Also, in pre-World War II Hawaii, off-duty military men regularly wore aloha shirts, which they called (now politically incorrect, of course) “gook shirts.” This practice was described in the James Jones novel, and shown in the film based on it.

A “broke-da-mout” piece of trivia, Drew. Thanks brah!